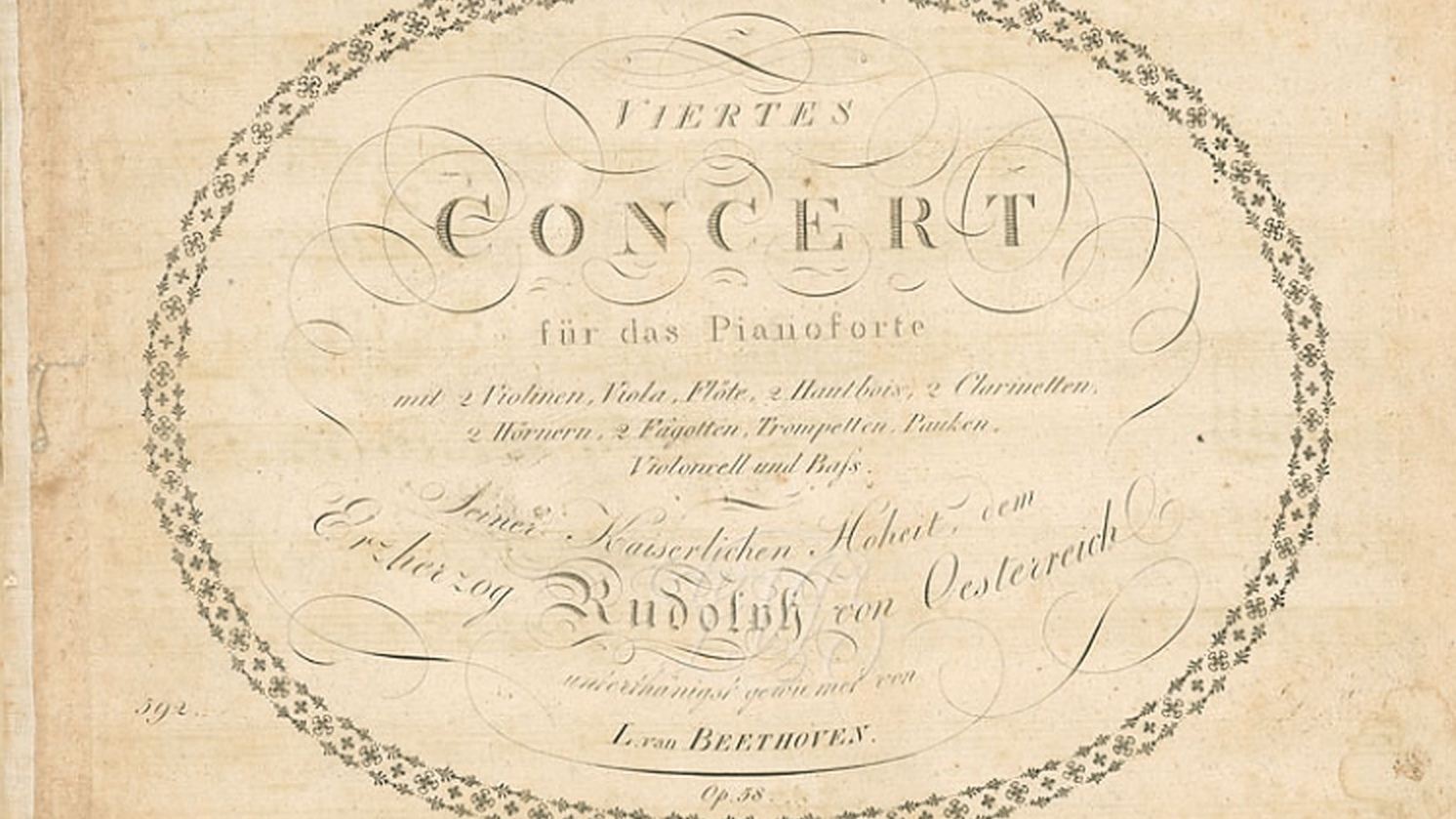

Each of Beethoven’s five mature piano concertos take us to a distinct place. The Third is set in a turbulent C minor, with a backward glance to Mozart. The Fifth, known as the “Emperor,” springs to life with a sense of monumentality and exhilarating heroism. In between is the sometimes overlooked Piano Concerto No. 4 in G Major.

Here, we enter a magical and quietly intimate world of shimmering colors. Musical lines unfold with the fluid inevitability of an improvisation. Most notably, in this Concerto a sublime and continuous dialogue between the solo piano and the instrumental voices of the orchestra emerges with striking clarity and drama. Glenn Gould wrote that it was here “that the ultimate of condensation, of unity with the solo exposition, of imagination, and of discipline was attained.”

The public premiere of Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto on December 22, 1808 was decidedly inauspicious. It was part of a four-hour-long marathon concert which took place at the unheated Theater an der Wien during a particularly frigid cold snap in Vienna. The under-rehearsed program included the Fifth and Sixth Symphonies, the concert aria, Ah! perfido, excerpts from the Mass in C Major, and the Choral Fantasy, which fell apart and had to be restarted. Regarding the concert, the German music commentator Johann Friedrich Reichardt wrote, “There we sat, in the most bitter cold, from half past six until half past ten, and confirmed for ourselves the maxim that one may easily have too much of a good thing, still more of a powerful one.” Although a May, 1809 review called it “the most admirable, singular, artistic and complex Beethoven concerto ever,” the Fourth Concerto suffered neglect until 1836 when it was championed by Felix Mendelssohn.

In the opening of the first movement, we are drawn into the Concerto’s intimate world in a convention-defying way. Instead of the customary extended orchestral introduction we would expect, for five serene bars the solo piano begins alone. The orchestra answers, taking the conversation in a new and unexpected direction which opens the door to the real introduction. As the movement unfolds, the solo piano dances amid the orchestral lines with glistening splashes of color and exuberant embellishments. Notice the recurring “short-short-short-long” rhythmic motif which returns in Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony.

In the brief second movement, the musical conversation takes a mysterious, even ominous turn. It begins with a stern E minor announcement in the strings, set in austere octaves. Strange allusions to operatic recitative may remind you of the final movement of the Ninth Symphony. In this drama there are two conversing “characters”—the quietly introspective solo piano and the gruff interjections of the strings. As the dialogue unfolds, the two disparate voices seem to find common ground. Over the tragic final chord, the solo piano reaches up in an arpeggio before falling back with three lamenting notes. The music commentator, David Ewen wrote, “There is perhaps nothing in all concerto literature to match the kind of philosophic dialogue that takes place for some seventy measures.” The German pianist, Wilhelm Kempff, observed, “On the two pages of full score which this movement occupies, there are few notes. Instead there are many rests, which sit like black, sinister birds on the lines of the music, signs signifying a silence which takes the breath away.”

The spell of the solemn second movement is broken with the arrival of the final movement. It’s a frolicking rondo filled with sparkling energy, humor, and virtuosity. A second theme (beginning around 1:08) anticipates the warmth and deep gratitude of the Ninth Symphony’s “Ode to Joy.” The coda surges to a sunny and exuberant conclusion.

I. Allegro moderato:

II. Andante con moto:

III. Rondo (Vivace):

Five Great Recordings

- Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 4 in G Major, Op. 58, Paul Lewis, Jirí Belohlávek, BBC Symphony Orchestra (2010 recording) Amazon

- Maria Joao Pires, Daniel Harding, and the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra (2014 recording)

- Evgeny Kissin, Colin Davis, and the London Symphony Orchestra (2008 recording)

- Pierre-Laurent Aimard, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, and the Chamber Orchestra of Europe (2002 recording)

- Emil Gilels, Georg Szell, and the Cleveland Orchestra (1968 recording)