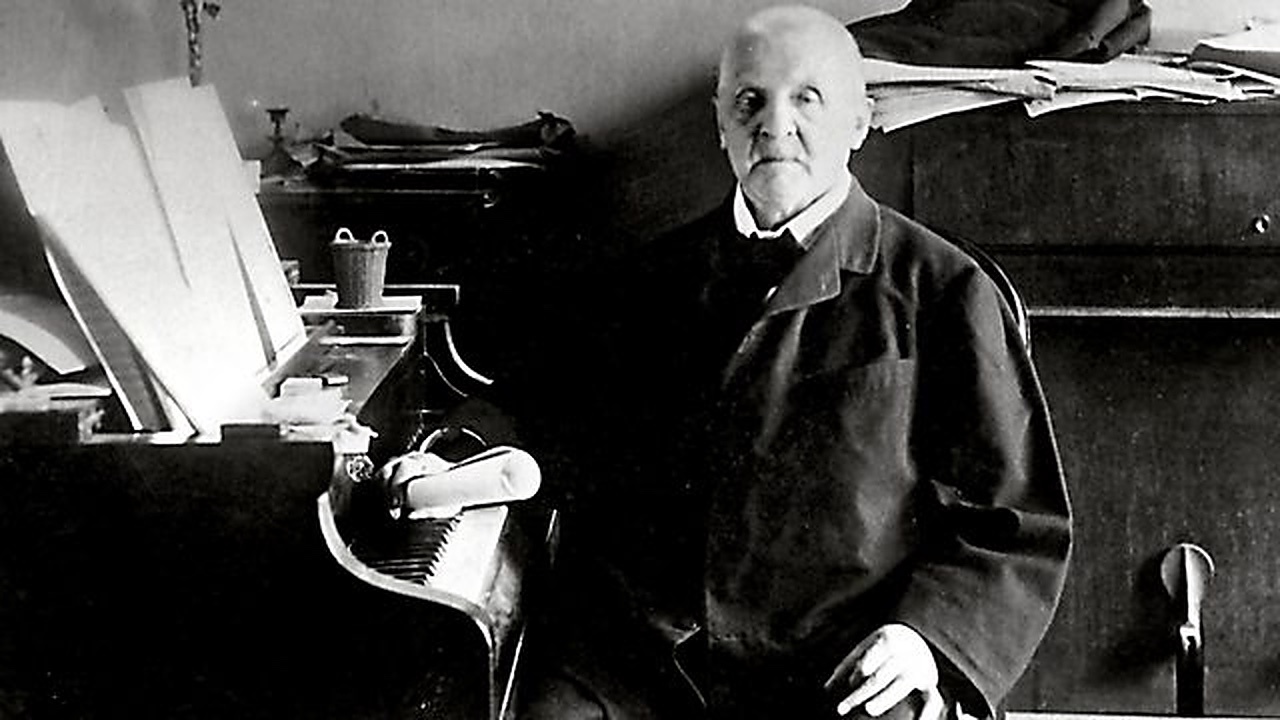

Gustav Mahler famously described Anton Bruckner (1824-1896), as “half simpleton, half God.”

Indeed, Bruckner was an eccentric figure marked by contradictions. Although he spent the latter part of his life in cosmopolitan Vienna, he never shed his rural Upper Austrian roots. An eminent organist who was long employed at the Augustin monastery of St. Florian, Bruckner was devout and unshakable in his religious faith. At the same time, he suffered periods of paralyzing personal and creative insecurity. Attacks from critics in Vienna’s politically charged environment and well-meaning critiques from friends led the naive and socially awkward Bruckner to make endless revisions of his works. Bruckner was a fanatical devotee of Richard Wagner, who boldly rejected the symphony as an outdated genre to be replaced by the operatic “music drama,” with its rich programatic associations. Yet, as a composer, Bruckner was drawn, not to operas and tone poems, but to the absolute music of the symphony.

With each of his symphonies, Bruckner returned to the same mystical starting point. Emerging out of silence, as if to turn up the volume on a cosmic work already in progress, this music seems to pick up where Beethoven’s monumental Ninth Symphony leaves off. Beethoven’s Ninth presented a daunting and enigmatic model which earlier composers avoided. Yet, as the musicologist Deryck Cooke noted, Bruckner arrived at a new kind of symphonic form:

Despite its general debt to Beethoven and Wagner, the “Bruckner Symphony” is a unique conception, not only because of the individuality of its spirit and its materials, but even more because of the absolute originality of its formal processes. At first, these processes seemed so strange and unprecedented that they were taken as evidence of sheer incompetence…. Now it is recognized that Bruckner’s unorthodox structural methods were inevitable…. Bruckner created a new and monumental type of symphonic organism, which abjured the tense, dynamic continuity of Beethoven, and the broad, fluid continuity of Wagner, in order to express something profoundly different from either composer, something elemental and metaphysical…his extraordinary attitude to the world, and the nature of his materials which arose from this attitude, dictated an entirely unorthodox handling of the traditional formal procedures. Sonata form is a dynamic, humanistic process, always going somewhere, constantly trying to arrive; but with Bruckner firm in his religious faith, the music has no need to go anywhere, no need to find a point of arrival, because it is already there…Experiencing Bruckner’s symphonic music is more like walking around a cathedral, and taking in each aspect of it, than like setting out on a journey to some hoped-for goal.

Bruckner’s Symphony No. 7 in E Major begins with a majestic and expansive melody in the cellos and solo horn, which rises over hushed violin tremolo. The melody, which purportedly came to Bruckner in a dream, is simultaneously serene, noble, and mysterious. Immediately, it begins to pull away from the “home” key of E major towards a rival key of B. In his book, Essence of Bruckner, Robert Simpson described the distinctive harmonic process of the Symphony’s first movement (Allegro moderato) as:

the slow evolution of B minor and B major out of a start that is not so much in as delicately poised on E major [and] the subtle resurgence of the true tonic, not without opposition from the pretender…outward resemblances such as the change from tonic (E) to dominant (B) must not deafen us to the fact that such behavior as we find in this opening section is totally uncharacteristic of sonata [form]. The slow emergence of one key, by persuasion, from a region dominated by another is a new phenomenon in the field of symphony, and the rest of this movement will be heard to reinstate E major in a similar but longer process.

In the second thematic group, the winds and strings converse as instrumental “choirs” in a way similar to the symphonies of Schubert. The third thematic group is heralded by the building tension of a mighty crescendo, punctuated by trumpet fanfares. It rises up with the awe-inspiring power of an architectural column in a vast edifice. At moments, Bruckner’s orchestra is transformed into a mighty pipe organ. The contours of his contrapuntal lines occasionally mirror each other to create a visceral sense of form and shape. For example, listen to the almost comical dialogue between the flute and low strings at (10:46). The coda section begins with a hushed “E” pedal tone in the timpani which continues for the remainder of the movement. In the strings, a solemn musical conversation emerges which is made up of haunting motivic fragments. Amid mounting intensity, the timpani rises up as a terrifying specter, almost overpowering the other voices before receding. It is in the final moments of the coda when the “home” key of E major is established for the first time with a majestic crescendo.

Moving to C-sharp minor, the second movement (Adagio: Sehr feierlich und sehr langsam) is solemn and majestic. For the first time in a symphony, we hear a quartet of Wagner tubas. Creating a dark, smoky sound, this instrument, which Wagner created for his Ring cycle, forms an acoustical bridge between the horn and the trombone. Bruckner composed this elegiac music between January and April of 1883 at a time when he was affected deeply by the death of Wagner. As the movement unfolds, a fragment of the opening chorale melody moves between instrumental choirs, resulting in a celebration of orchestral color. The tender, forward moving second theme recalls the similarly flowing second theme of the Adagio of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Following the completion of the score, a cymbal crash and triangle were added at the movement’s climax. Later, this addition was marked “invalid,” although not in the composer’s hand. Some conductors choose to include the added percussion, while others omit it, opting for a more organ-like sound. In the coda section, the strings enter into a dreamy, lamenting conversation with the flute and oboe. The final statement of the chorale brings the reassurance of C-sharp major.

Set in A minor, the Scherzo takes flight as a supernatural dance in triple meter. It’s a thrilling adventure, propelled forward by a persistent rhythmic motif in the strings. Heroic statements in the solo trumpet are joined by the horns and trombones amid quirky woodwind interjections. The trio section in F major brings a warm and nostalgic contrast.

The opening theme of the Finale contains echoes of the first movement’s principal theme. Now, the original theme’s ascending line leaps forward with jubilant dotted rhythms. The second theme is a serene chorale, propelled forward by a walking bass line in the low strings. The brass section becomes a majestic pipe organ. We can imagine Bruckner engaged in a triumphant organ improvisation which develops all of the movement’s motifs. The coda arrives with a moment of strikingly dissonant voice leading. A final, triumphant crescendo reaffirms the primacy of E major, and a cosmic return “home.”

Here is a 1999 performance featuring Günter Wand and the NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchestra:

Here is a 1990 performance by Sergiu Celibidache and the Munich Philharmonic:

Five Great Recordings

- Bruckner: Symphony No. 7 in E Major, Günter Wand, Berlin Philharmonic Amazon

- Herbert Blomstedt and the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra

- Herbert von Karajan and the Vienna Philharmonic

- Bernard Haitink and the Royal Concergebouw Orchestra

- Klaus Tennstedt and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (1984 live radio broadcast) part 1, part 2

Fascinating Tim… thank you for reminding me of the need to learn the Bruckner symphonies. I know they’re important but they still lie waiting. I’ve spent the past 3-4 years learning the Mahler, Sibelius, and Shostakovich symphonies – soon, thanks to your prompting, it will be time for Bruckner. I recall there are two Bruckner symphonies on the top 20 all time greatest symphonies as chosen by 150 of the world’s conductors. They must know.

Just a modest suggestion, Timothy, if I may please make. A connection to Linked In would work well for you. It’s an adult portal with an enormous scope of people who would I think be interested in your blog. I do circulate your posts on Linked In but so much easier and directly attributable to you were you to provide a link. And my goodness do we ever need the therapeutic qualities of music more than at time like this?

Hi Johnston, There is a Linkin share option above in the social media strip. It is past the “plus” sign, which expands the strip. Thank you for sharing the posts!

It is truly a masterpiece, performed by Arthur Nikisch at its magical premier in Leipzig. I believe in Bruckner’s original version. It is not clear whether he approved of the triangle and cymbal crash in the adagio added later. I think unlikely. I’ve written about it in my novel about the master entitled. ‘Anton Bruckner – an emerging genius’, to be published this year, his 200th anniversary.