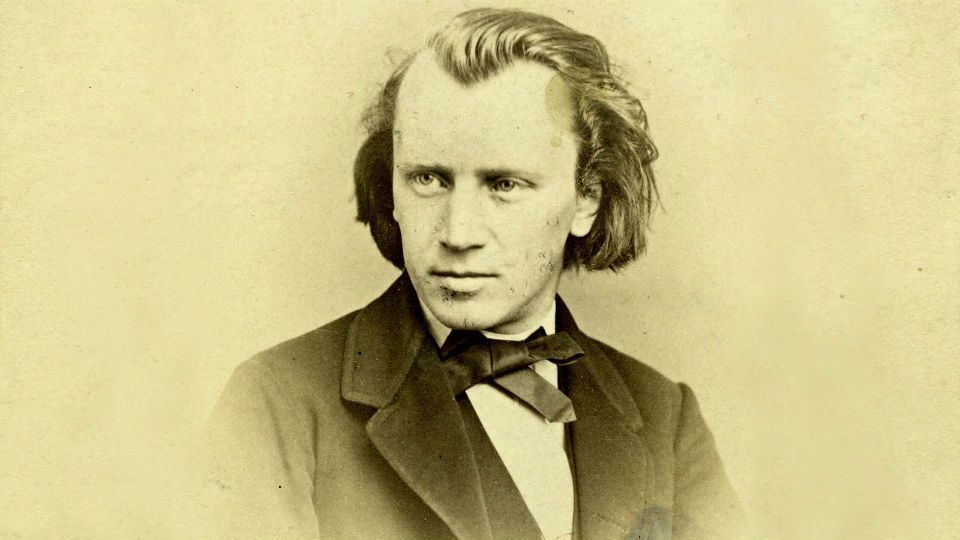

In 1875, Johannes Brahms sent the newly completed score for his C minor Piano Quartet to his publisher, Fritz Simrock, with the following message:

On the cover you must have a picture, namely a head with a pistol to it. Now you can form some conception of the music! I’ll send you my photograph for the purpose. Since you seem to like color printing, you can use blue coat, yellow breeches, and top-boots.

It was a tongue in cheek reference to Goethe’s 1774 epistolary novel, The Sorrows of Young Werther, in which the Romantic hero commits suicide after falling in love with a married woman whose husband he admires. Piano Quartet No. 3 in C minor was the last to be published of Brahms’ contributions to the genre. Yet, its first version, which preceded the other two quartets, was completed in 1856 at a time when the 23-year-old composer had become devoted to Clara Schumann. While Robert Schumann spent his final years languishing in an asylum amid deteriorating mental health, Brahms assisted Clara in taking care of the Schumann household. Obvious parallels can be drawn between Brahms’ deep affection for Clara and the emotional tumult of the fictional Werther.

Dissatisfied with the work in its original form, Brahms set it aside. Twenty years later, the mature piece emerged. Originally set in C-sharp minor, the final version moved down a semitone to tragic and lamenting C minor, the key of Brahms’ First Symphony. The original finale was transformed into the Scherzo, and the concluding two movements were newly written. Still, the turbulent passions which swirled around the piece at its inception remained.

The first movement (Allegro non troppo) begins with octave C’s in the piano, followed by tragic “sighs” in the strings which seem to intone the name, “Clara.” It’s a motivic kernel which develops into a transposition of the four note descending “Clara Theme” (E-flat, D, C, B, C), the motif which haunts so much of the music of Robert Schumann. These gloomy opening bars undergo a harmonic “descent.” The first theme is launched into motion with the jarring, dissonant interruption of a rising octave E pizzicato in the viola and violin. The remainder of the tempestuous movement alternates between ferocity and soaring passion. The recapitulation drifts into mysterious territory which fails to establish fully the home key of C minor. The coda’s tragic final cadence leaves the tension unresolved.

The Scherzo returns to C minor, as if to “[furnish] the tonal balance unprovided for by the end of the first movement.” (Donald Francis Tovey) It unfolds as a thrilling, frenetic musical conversation. We are denied the relief of a contrasting trio section. Instead, a ferocious development section takes hold.

Moving to the remote key of E major, the third movement (Andante) is a tender love song without words. The warm first theme is introduced by the cello, and then becomes a sensuous duet between the cello and violin. This music gives us a sense of deep yearning, mystery, and shimmering transcendence. The final bars are a poignant farewell.

The final movement (Allegro comodo) returns to tempestuous C minor. In the opening bars, the piano’s undulating lines echo the opening of Mendelssohn’s Piano Trio in C minor, Op. 66. The fateful “short-short-short-long” motif of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony (also in C minor) lurks in the shadows of the inner voices. This rhythmic motif becomes more bold as the movement continues. It haunts the music as a persistent musical ghost. There are allusions to the “sighs” of the opening movement, as well as the “Clara Theme,” which is heard in retrograde in the violin (B, C, D, E-flat, F, E-flat). The second theme moves to the relative major with a chorale theme which is heard in the strings amid playful ripples in the piano. The coda drifts into quiet resignation and exhaustion. A forte cadence in C major brings the Quartet to an abrupt conclusion.

The “Werther” Quartet, as it has come to be known, was premiered in Vienna on November 18, 1875 with Brahms at the piano alongside members of the Hellmesberger Quartet.

I. Allegro non troppo:

II. Scherzo. Allegro:

III. Andante:

IV. Finale. Allegro comodo:

Recordings

- Brahms: Piano Quartet No. 3 in C minor, Op. 60, Trio Wanderer, Christophe Gaugué harmoniamundi.com

- Beaux Arts Trio, Walter Trampler

- Renaud Capuçon, Gautier Capuçon, Gérard Caussé, Nicholas Angelich