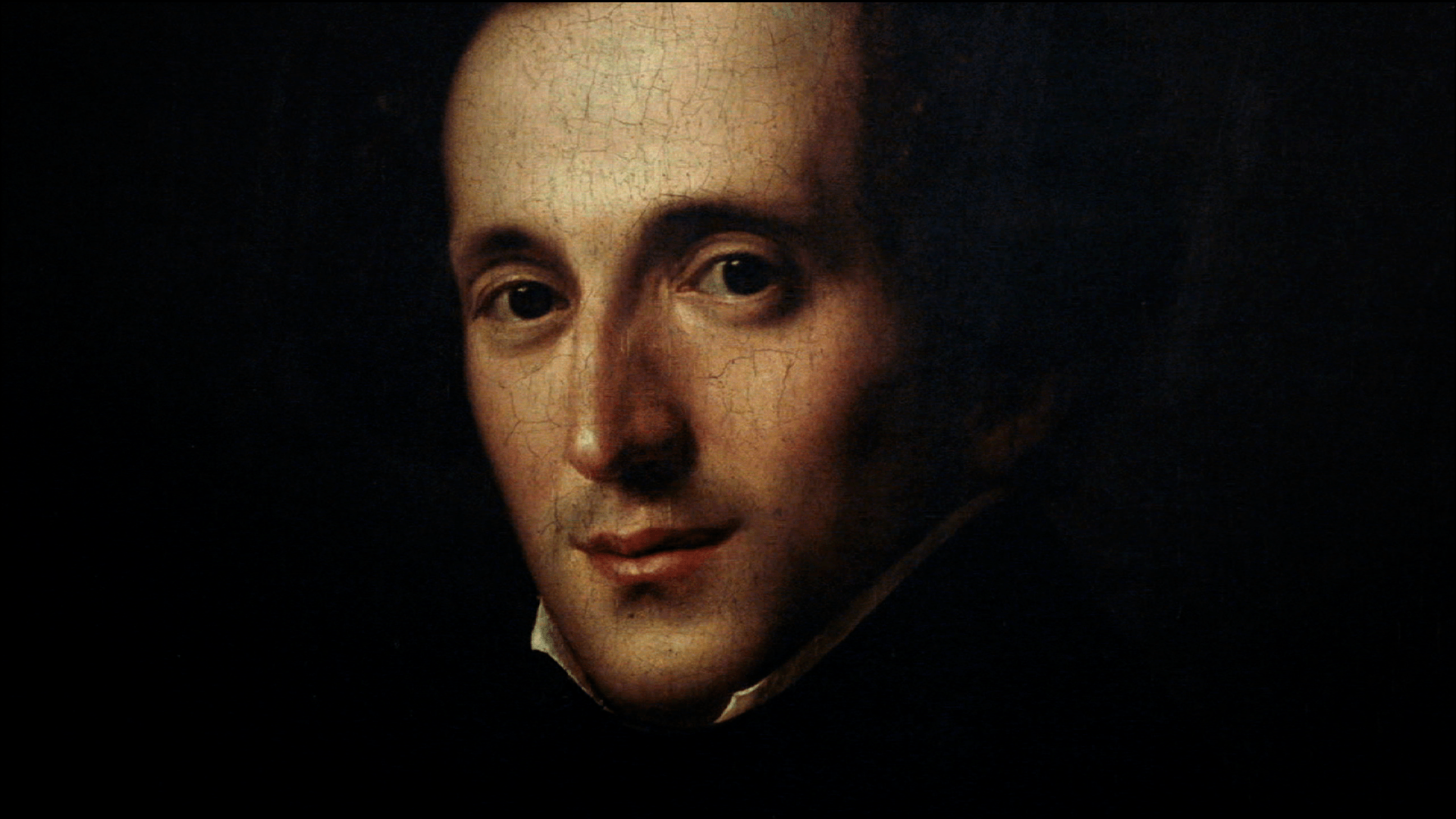

In the music of Felix Mendelssohn, two aesthetic worlds meet. The mystery and pathos of Romanticism blend with the pristine formal constructs of Classicism. Robert Schumann summarized this unique synthesis when he called Mendelssohn “the Mozart of the nineteenth century, the most illuminating of musicians, who sees more clearly than others through the contradictions of our era and is the first to reconcile them.”

This remarkable synthesis can be heard in Mendelssohn’s Piano Trio No. 2 in C minor. Completed in 1845, two years before the composer’s death at the age of 38, it was the last chamber work that Mendelssohn lived to see published. He dedicated the score to the violinist and composer, Louis Spohr, and presented it to his sister, Fanny, as a birthday gift.

The first movement (Allegro energico e con fuoco) begins with the hushed suspense of a ghost story. Restless, tempestuous lines rise and fall in a tense whisper. We encounter something similar to the mysterious, windswept landscape of The Hebrides. The music is propelled forward by nervous, undulating lines in the piano which, at moments, leap out in glistening arpeggios. Thirty years later, Johannes Brahms would return to these lines in the finale of his Piano Quartet in C minor, Op. 60. The first theme developed from Mendelssohn’s haunting Song Without Words, Op. 102, No. 1. The second theme arrives in a sudden, triumphant burst before drifting off into moments of gentle repose. There are thrilling homages to the architectural counterpoint of J.S. Bach, with outer voices unfolding in mirror image. In the coda, the persistent opening motif can be heard at two rates of speed, simultaneously (9:15). The music surges towards its final cadence with ferocious passion.

The second movement (Andante espressivo) enters the world of song with a tender lullaby. Its rocking motion has reminded some listeners of Mendelssohn’s Song Without Words, Op. 19, No. 6 (“Venetian Boat Songs”).

The fleeting Scherzo takes us to the magical, nocturnal fairy world of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Mendelssohn acknowledged that, technically, this scurrying music might be “a trifle nasty to play.” With pizzicato, the final bars fade into the shadows of the forest.

The Finale (Allegro appassionato) takes a journey from the tempestuous anxiety of the opening movement to triumphant C major. Along the way comes a soaring quotation of the Lutheran chorale melody, Gelobet seist Du, Jesu Christ, commonly known in English as Old Hundredth.

I. Allegro energico e con fuoco:

II. Andante espressivo:

III. Scherzo. Molto allegro quasi presto:

IV. Finale. Allegro appassionato:

Recordings

- Mendelssohn: Piano Trio No. 2 in C Minor, Op. 66, MWV Q33, Julia Fischer, Daniel Muller-Schott, Jonathan Gilad pentatonemusic.com

- Trio Wanderer (2007 recording)

- Lionidas Kavakos, Gautier Capuçon, and Yuja Wang (concert recording)